Wittgenstein and LLMs

I stumbled upon a conversation about LLMs in connection with Wittgenstein, the question whether LLMs are intelligent and how they relate with LLMs.

When I was about halfway through what I wanted to write in my response, I noticed I was already 700 characters over the limit. So I’ll post my thoughts about the matter in a substack thread instead.

The main point I want to make is that I don’t believe it makes sense to cite Wittgenstein to conclusively answer whether LLMs are intelligent or whether LLMs are language game players.

LLMs are not Frankenstein monsters, they are Wittgenstein monsters.

They are also a critique of the Analytic reading of Wittgenstein (a distinction clarified thanks to Prof. Mireille Hildebrandt) and subsequent computational linguistics built on linguistic idealism (the view that meaning needs no grounding in a reality beyond language itself), if someone needs more evidence against this extractive reading of Wittgenstein. They provide a refutation because even though they simulate language games in a vacuum, without being grounded in Lebensform, they are clearly not intelligent.Post on LinkedIn, by Ali Pasha Abdollahi

playing a language game assumes intelligence, so no, LLMs don’t play - they merely simulate

Thank you for this excellent point. Playing suggests intentionality and being situated in context. I certainly do not want my critique of Wittgenstein to provide fuel for AI hype. He was influential, I think, by inspiring that “meaning is use”, that one may take “use” out of social human context, simulate “use” and try and build machines that produce text without being grounded in reality. In other words, he may have provided the initial fuel for machines of simulating syntax with no semantics.

LLMs are a notorious target of discussion when it comes to Wittgensteinian philosophy. One can argue endlessly about whether they’re intelligent or not.

I’m not a philosopher in a traditional academic sense, but I am someone who is fascinated by the way Wittgenstein looks at the world, and I hope by taking on his perspective as much as I can, I’ll open up the avenue for exploration, rather than answers.

What I noticed in particular with LLMs is that they can follow the rules of conversation. You can play rock, paper, scissors with them, talk about the weather, have a topic explained to you, reflect on the news together. This is entirely in line with what Mireille stated in the thread

Playing a language game assumes intelligence, so no, LLMs don’t play - they merely simulate

Despite their producing language, LLMs lack intention, agency and goals1. This shows most clearly by how they never stop playing the exact game or initiate a game of their own. They are clearly capable of being part of a conversation in some sense of the word, but they - unless explicitly prompted to do so - will not steer the direction of the conversation out of their own volition.

This is very reminiscent of Peter Suber’s nomic game. I’m not sure if this is conceptually in-line with how Wittgenstein views language games, but a common viewpoint I’ve seen in contemporary philosophy is that “being a participant in a game means being able to talk about and change the rules of the game”, like in Nomic:

Nomic is a game in which changing the rules is a move. In that respect it differs from almost every other game. The primary activity of Nomic is proposing changes in the rules, debating the wisdom of changing them in that way, voting on the changes, deciding what can and cannot be done afterwards, and doing it. Even this core of the game, of course, can be changed

I’m not so sure whether we can answer questions using Wittgensteinian philosophy about machine intelligence and whether they’re participants of language games. Primarily because Wittgenstein’s entire method revolves around the living quality of language:

“To imagine a language means to imagine a form of life.” (§19)

I don’t know how you interpret this quote, but I’ve always understood it as him trying to say that language isn’t ever a concrete, hard, objective thing with clear rules and structure. It’s messy, incredibly messy. It’s subject to a form of evolutionary pressure, it changes over time, the same word can mean a different thing in a different context. Words take on new meanings with time. It is “of the same stuff” as life itself.

From that perspective, I’ve always seen language as a mirror of how people live. If someone says their dog is intelligent, that doesn’t mean - in a traditional cognitivist sense - that they’re making a propositional truth claim about the dog’s intelligence.

(Late) Wittgenstein is rarely black or white in his thinking, his primary mode of inquiry seems to be to ask questions, to get ever closer to the depth of the world without risking losing yourself to an absolutist perspective that keeps you trapped

“To show the fly the way out of the fly bottle“

What does Wittgenstein himself say about other minds? About machine or otherwise alien intelligences? About non-human language game participants? Let’s open Philosophical Investigations and take a look!

“Could a machine think?—Could it be in pain?—Well, is the human body to be called such a machine? It surely comes as close as possible to being such a machine.

But a machine surely cannot think!—Is that an empirical statement? No. We only say of a human being and what is like one that it thinks. We also say it of dolls and no doubt of spirits too.” (§359-360)

“We also say it of dolls and no doubt of spirits too”.

This kind of a passage exemplifies how Wittgenstein’s mode of inquiry works. Observe how language is actually used in the real-world. Some people most certainly do call dolls and spirits intelligent. Does that make them intelligent? Again, I claim the answer isn’t an answer, the answer is to ask another question. The road we walk is what Wittgensteinian philosophy entails.

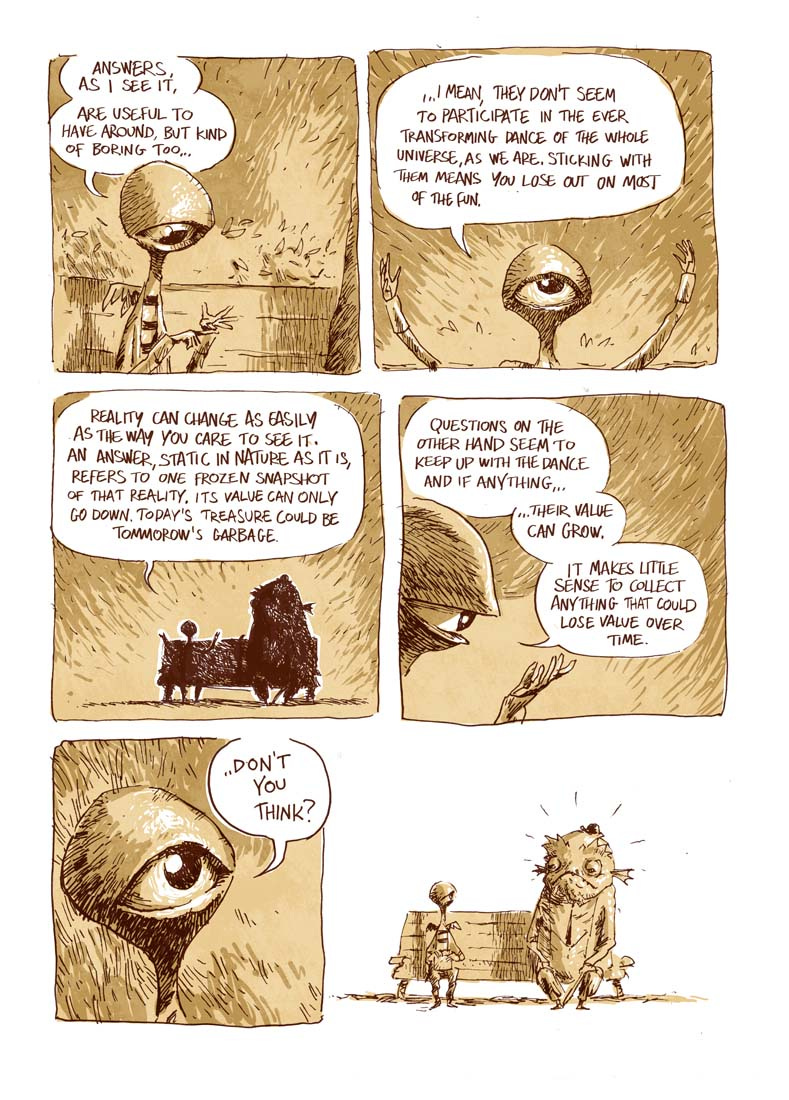

I cannot think of a better representation of Wittgenstein’s way of doing philosophy than through this panel:

I don’t know if I’m an odd one out with respect to how I read Wittgenstein, or that it’s just the way philosophy is traditionally practiced that we feel the need to find definite questions to answers through the citing of philosophers long gone.

How I’ve personally read Wittgenstein isn’t that we should have absolute answers to questions, these change as life around us change. The way Wittgenstein looked at language always very strongly reminded me of how biologists look at animals - just observe it and ask questions. Life is absurdly complex and there simply are no absolutes in biology, and language - in my interpretation of Wittgenstein - is just as much part of biology.

I find it very notable that there are many people who view LLMs as having agency or intention. Might that be because the LLM has agency or intention? Or is it because we’re projecting it onto the machine? Does the doll have agency or intention? Or are we asking questions that make us fly back into the fly bottle?

A more notable passage also touches on the same topic:

“First I need to remark that I am not counting the understanding of what is read as part of ‘reading’ for purposes of this investigation: reading is here the activity of rendering out loud what is written or printed; and also of writing from dictation, writing out something printed, playing from a score, and so on.”

“Consider the following case. Human beings or creatures of some other kind are used by us as reading-machines. They are trained for this purpose. The trainer says of some that they can already read, of others that they cannot yet do so. Take the case of a pupil who has so far not taken part in the training: if he is shown a written word he will sometimes produce some sort of sound, and here and there it happens ‘accidentally’ to be roughly right. A third person hears this pupil on such an occasion and says: ‘He is reading’. But the teacher says: ‘No, he isn’t reading; that was just an accident.’—But let us suppose that this pupil continues to react correctly to further words that are put before him. After a while the teacher says: ‘Now he can read!’—But what of that first word? Is the teacher to say: ‘I was wrong, and he did read it’—or: ‘He only began really to read later on’?—When did he begin to read? Which was the first word that he read? This question makes no sense here.“ (§156-157)

When reading this passage, do you get the sense that Wittgenstein is the kind of person to give a definite answer to the question of whether machines can think?

Let me cite an LLMs understanding of what this passage means: The point is the question of what counts as reading cannot be settled by looking inside the creature. For the sake of this conversation, I asked Claude to comment on the passage. I believe this passage is relevant to the conversation, and I am making a deliberate choice to weave it into this article.

Now that I, a human, have repeated what an LLM has repeated, is it part of a language game? Or is that sentence somehow different? Are you sure I wrote this article, and didn’t have an LLM write the entire thing?

I digress.

Is that also what you get out of this passage? That what counts as reading cannot be settled by looking inside the creature? I believe Wittgenstein left these passages open deliberately so we may ponder them and participate in the ever transforming dance of the whole universe.

In Philosophical investigations, Wittgenstein introduces languages games as being not dissimilar to a game of chess. It has participants, rules, pieces, moves that you can take, and in different cultures perhaps people play with slightly different rules. What constitutes a game exactly is fuzzy, it has no clear boundary.

What I imagine when I think about the situation we find ourselves in isn’t the need to find an answer to the question of whether machines are intelligent or not. What I find much more interesting is to pose a diverse set of questions so we may hope to see things in different ways, so we may experience the world around us in manners we haven’t before. To perhaps write a sentence you’ve never written before, to think a thought you’ve never thought before.

Considering the chess-as-language-game metaphor, what if we replaced our knights with “smart knights”? Knights that have a camera, and use the magical powers of the cloud and LLM to blink a little LED light when they want to indicate something to the player. They might flash red when the player is about to make a move the LLM wants her to reconsider, or they might blue when they “want” to move.

Are we still playing chess? Or are we playing an entirely different game? I find the situation not dissimilar to the situation we find ourselves in in real-life.

Even if LLMs themselves aren’t direct participants in language games, they directly change the way how we play the games ourselves. Does that make them participants? Why not? Wittgenstein seems to think these questions worth pondering:

From this perspective, one might just as well argue a calendar is part of a language game, and I think there is merit to saying they are. Perhaps not as as a participant (I find it hard to believe so!), but how about as a piece on the chessboard? What if our proverbial calendar starts talking back to us thanks through the magic of LLMs?

- Color samples: “are they part of the language? Well, it is as you please.” (§16)

“’But in a fairy tale the pot too can see and hear!’ (Certainly; but it can also talk.)

‘But the fairy tale only invents what is not the case: it does not talk nonsense.’—It is not as simple as that. Is it false or nonsensical to say that a pot talks? Have we a clear picture of the circumstances in which we should say of a pot that it talked? (Even a nonsense-poem is not nonsense in the same way as the babbling of a child.)

We do indeed say of an inanimate thing that it is in pain: when playing with dolls for example. But this use of the concept of pain is a secondary one.“ (§282)

I find it hard to quote explicitly a passage that says what I want to say, but I believe that what Wittgenstein is trying to say is that even the supposed “clean” rules of a “Wittgensteinian” language game are as “clean” as the water of a lake observed under a microscope. It’s a mess, a beautiful living mess, the best we can do is observe and ponder.

Observe and ponder.

There are some exceptions like protecting constitutional boundaries, for example, Claude’s “Constitutional AI” allows the LLM assert ethical boundaries. Similarly, Claude has been given the ability to end conversations.